Happy Boxing Day! Oh, I know it's still Christmas for some of you guys in the Western Hemisphere, but I'm well in the East, both physically and literarily. In fact, I've drifted all the way out to the Pacific, back to Oceania, where there's an obscure US territory called the CNMI, full of Chamorro-speakers, known primarily for its nearby trench.

What most folks don't know is that the biggest island of the Marianas spent the first decade of the 21st century trying to get into the industrial age, importing loads of low-cost Chinese and Filipina women to work in garment factories so they could turn out Osh Kosh B'Gosh products printed "Made in the USA".

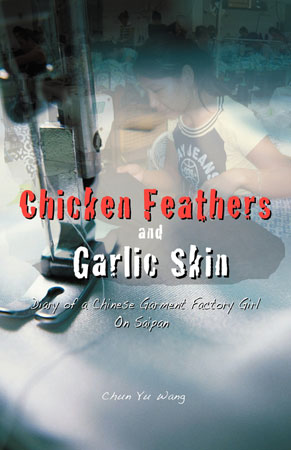

Hence the story above: a true-life tale of a 25 year-old Wuxi woman who went to Saipan to spent nine years of her adult life breaking her back over sewing machines. It's a weird kind of memoir: one of those situations in which a guy tries to make the subaltern speak (the initiator and editor of the book is the Jamaican-American-Saipanese journalist Walt F. J. Goodridge).

But Wang (yes, her surname is Wang, not Chun) is no hick either: she left her video-game playing husband in her home country because factory work in the Marianas was marginally better-paying, and took enough English courses to be able to translate her Mandarin manuscript to Goodridge, one-to-one.(He was fascinated by the Chinese idioms she used - the title, of course, is a transliteration of 鸡毛蒜皮 - even though these sound a tad hackneyed, even clichéd, to bilinguals.)

Frankly, the book isn't a must-read. It's an interesting look at the world of contemporary Chinese migrant labour, showing their aspirations and their sweat and their abuse from crooked overseers and their losses from burglars and accidents at home and worthless husbands and cops who claim they'll get them a green card and then disavow ever having received any payment.

Of course Americans are shocked by the suffering. But as a Singaporean, who's descended from and surrounded by migrant Chinese labour, I'm often thinking, "Meh. I've heard worse."

Which is horrible of me of course - recent events have thrust these marginalised workers into the spotlight, and we have to do something about it, if only to show that we're a society that treats people with humanity. But specifically regarding this book: Wang had her own home, free English lessons and the ability to quit her nasty factory jobs and search for new (usually equally bad) ones. Blue-collar foreign workers in Singapore just don't have those rights.

The interesting thing about a situation like this is that it shows how the oppressed masses aren't necessarily just victims. Wang and many other workers protest, walk out, steal and shag around to get what they want. And even when all the factories close (towards the end of the 2000s, costs rose and competitors like Vietnam became more attractive), Wang and her sisters realised they wanted to stay on, because they'd experienced freedom from their families and their obligations on this tiny, tropical island, and even if their sons were waiting for them at home, the only way to live for themselves was to be bad mothers, staying alive in the foreign sun.

Also - unrelated to workers' rights - one does get the sense that Wang isn't a particularly nice person. In her home, and at virtually every workplace, she's fighting with people, she's dissatisfied. Wherever you go, there you are, as they say.

View Around the World in 80 Books!!! in a larger map

Representative quote: Little by little, over the years and because of my trusting and kindness, I have lost most of my money. In all the years I worked, and all the money I earned, I accomplished nothing. In China, we would say, I added frost to snow. Adding frost to snow means "engaging in a futile, meaningless action that adds no visible benefit." That's what all my years of work on Saipan have been.

Next book: Tanya Chargualaf Taimanglo's Attitude 13: A Daughter of Guam's Collection of Short Stories, from Guam.

No comments:

Post a Comment